The story of my acquaintance with Moses Feigin is very simple. Art critic Vladimir Kostin and artist Mikhail Ivanov were the initiators of the exhibition of Feigin and his neighbor in the workshop of Vladimir Fedotov. The text to Fedotov's catalog, which, unfortunately, did not live up to the exhibition, was written by Vladimir Yumatov, but Feigin's art was closer to me.

In my diary for December 1978, I found quick sketches that I made while viewing Feigin's paintings, as well as short remarks and explanations of the artist and everyone gathered in the workshop. Kostin then advised me to give the article a title - “Dynamics. Music. Color". But since the text was intended for a catalog, and not for a newspaper or magazine, the need for a title disappeared.

The show lasted quite a long time. A series of abstract and figurative paintings, unexpected in freedom and internal energy, were built, a whimsical world of the circus, dramatic compositions dedicated to the revolution, war, and the world of arts were built. Looking at the variety of themes and plastic solutions, Kostin ironically remarked; “And once I wrote the cast iron spill, factories…”. To which Ivanov immediately reacted: "And they helped him". Indeed, Feigin later confirmed that the enchanting spectacle of pouring fiery metal was for him not a routine production topic, but an artistic event.

In fact, the event for Feigin was the entire XX century he lived with all its terrible upheavals. Lying in the hospital, the artist once witnessed how "an old Budenovite who raved and commanded was dying." At the same time, the idea of one extremely expressive abstract composition dedicated to the Civil War arose.

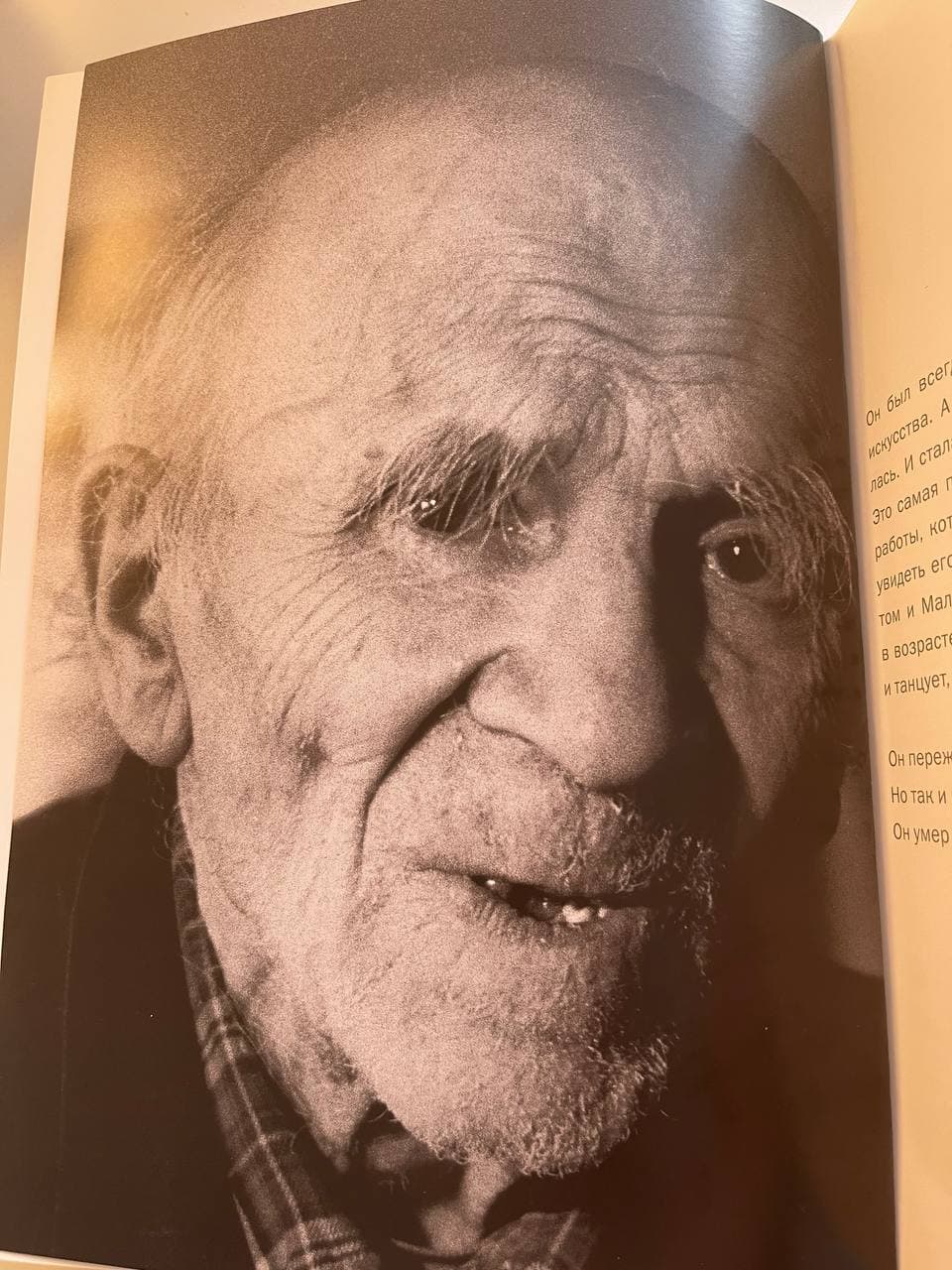

Even if you just list the names of some paintings and series, you can understand how wide and varied the range of interests of the artist who conducted his "Conversation with God", with Charlie Chaplin, with the heroes of P. Bulgakov, with his own memory, was. On one of my visits, I came to the studio with the photographer Lev Melekhov, who took several successful black-and-white photographs of Feigin, who always wore a light visor that protected his sore eyes from bright light. Together with a long apron and a work blouse, despite the fragility of his figure and small stature, he seemed to be a real knight of painting. Bright colors on a dark background reminded of glowing medieval stained-glass windows, and everything in general remained in the memory for a long time like the works of monumental artists. The modest size of the paintings did not in the least cancel this impression.

During a discussion of a one-day exhibition in a club of Moscow painters in December 1978, Mikhail Ivanov, looking at the work of artists of different generations, said: "Here is Feigin, Fedotov, but can't you say that this was written by each of them after seventy ..." And indeed painting and graphics Feigina are extremely emotional. Sometimes, not satisfied with the natural strength of a particular paint or monk, he uses various additional lining materials. Silver and gold foil, for example; writes not only on the vibrating surface of the canvas, but also on plywood, hardboard, cardboard or simply on thick paper, using its smooth or rough surface, color or geometric background. His technical arsenal is no less diverse in graphics, where, in addition to classical materials such as ink, watercolor, gouache, pastel, charcoal and reactive printing ink are used. In addition, not being limited to the real-life subject range, Feigin creates his own surroundings for still lifes. For example, some still lifes from 1966 and subsequent years are composed of homemade painted wooden figures and masks, reminiscent of African plastic. Perhaps this was the effect of a long-standing love for such a miracle worker of the 20th century as Picasso.

But other variants of sympathies and hobbies are not excluded, as well as an example of well-known domestic masters such as Alexander Tyshler, Ilya Tabenkin, Evgeny Rastorguev. “We were considered a spoiled generation,” said Feigin, recalling the first post-war decades, when his peers and more young artists turned not only to world art of the 20th century, but also remembered the glorious names of Russian painters, graphic artists and sculptors. The need to restore the "connection of times", the connection with the "Silver Age" and the art of subsequent years, up to 1932, after which the bright and rich life of various groups and trends was almost finished, and the rut of "socialist realism" began to roll hard.

Feigin did not speak at noisy meetings and discussions of exhibitions, did not write declarations and was generally quiet and hardly noticeable in the outer life of the Moscow Union. His doubts, struggles and passions were fully realized within the walls of his own apartment, where he lived and worked, and then in the workshop at 65 Vavilov Street, which he received with Fedotov only in 1964, when he was 60 years old. “It’s probably hard for you to imagine what this workshop was for me, - the artist said, - I ran into it in the morning, like they run to their mistress ...” Non-existent discussion clubs and professional discussions replaced arguments and conversations with a friend who worked next to behind a curtain. Their communal workshop and the difference in temperament did not interfere with mutual understanding and creativity itself.

Behind Feigin's shoulders were the happy years of youth and communication with the leading masters of the Jack of Diamonds. In particular, the mighty Aristarkh Lentulov was very close to the artist. Feygin repeatedly recalled and told how the "diamonds" loaded their paintings onto a cart, and he accompanied them to the exhibition hall. In his older companions in art, he was attracted not by the outward "booth rudeness" and shocking of the bourgeois public. In the 1920s and early 30s, while studying at the Vkhutemas, he absorbed like a sponge the inner visual culture that the leading masters of that charge inherited and carried within themselves. In particular, his teachers were Ilya Mashkov, Alexander Osmerkin, Lyubov Popova.

In the 1940s and 50s, there could be no question of openly showing at exhibitions any works of an experimental plan and, in general, something unrealistic. This would immediately be defined as "formalism" with all the ensuing consequences, which, incidentally, happened during the much more vegetarian "thaw" times in the early 60s, when at the exhibition "30 Years of the Moscow Union of Artists" and immediately after it happened as then they joked sadly, "harassing the obstinate and beating up the unknown".

From the works of 1946 preserved in the family (Children at the Balcony, Annochka), one can judge the picturesque quality and professionalism of Feigin the realist, who found for himself his chamber human scale of the reflection of the environment, without falling into thematic rhetoric and false pathos that abounded at the official exhibitions of those years. At the end of the next decade, he also naturally wrote the workshops of the Hammer and Sickle factory, admiring the collision of warm and cold colors and unexpected shapes. In fact, painting with all its magic and treasure has always outstripped any "subject" in Feigin.

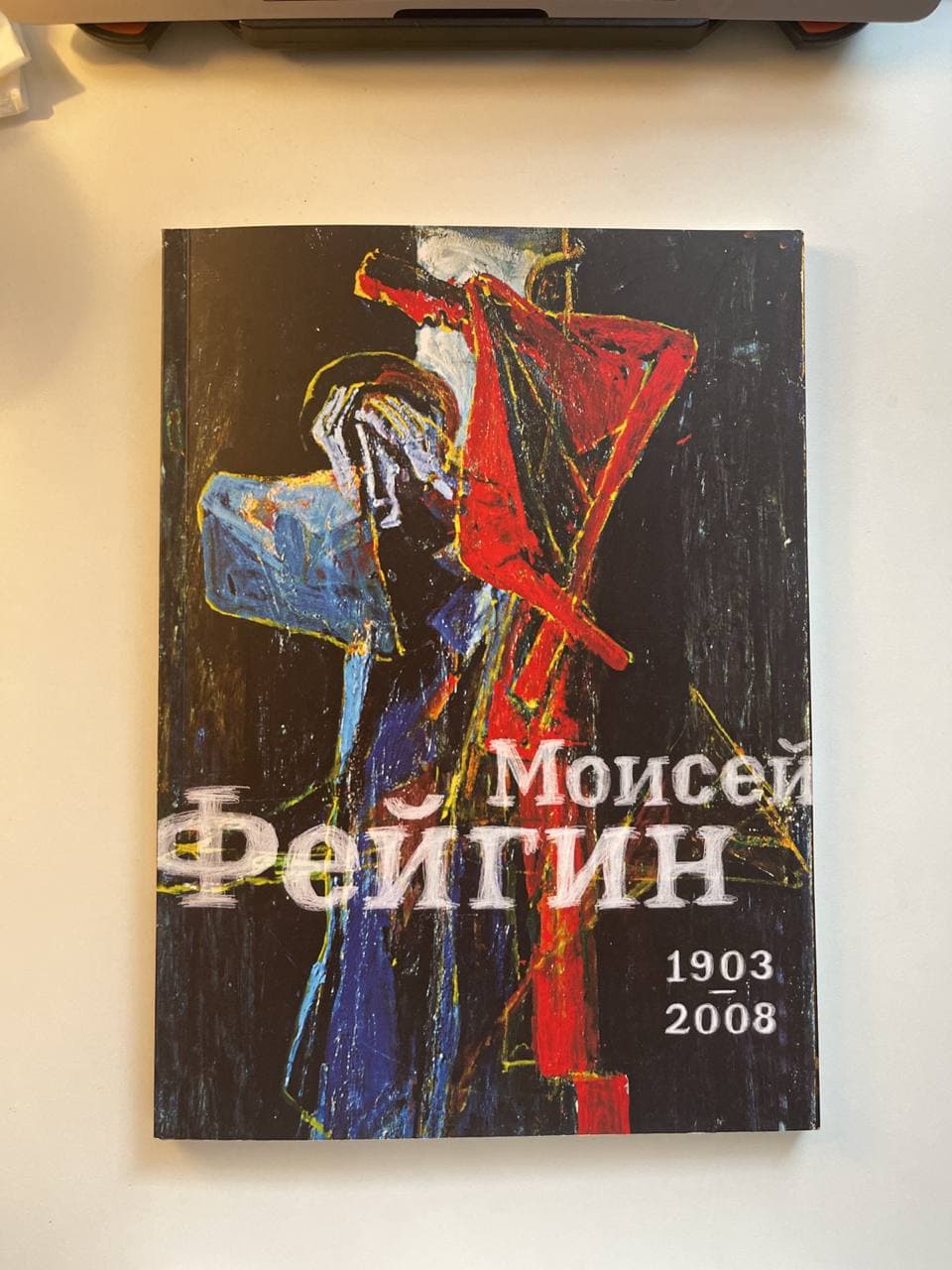

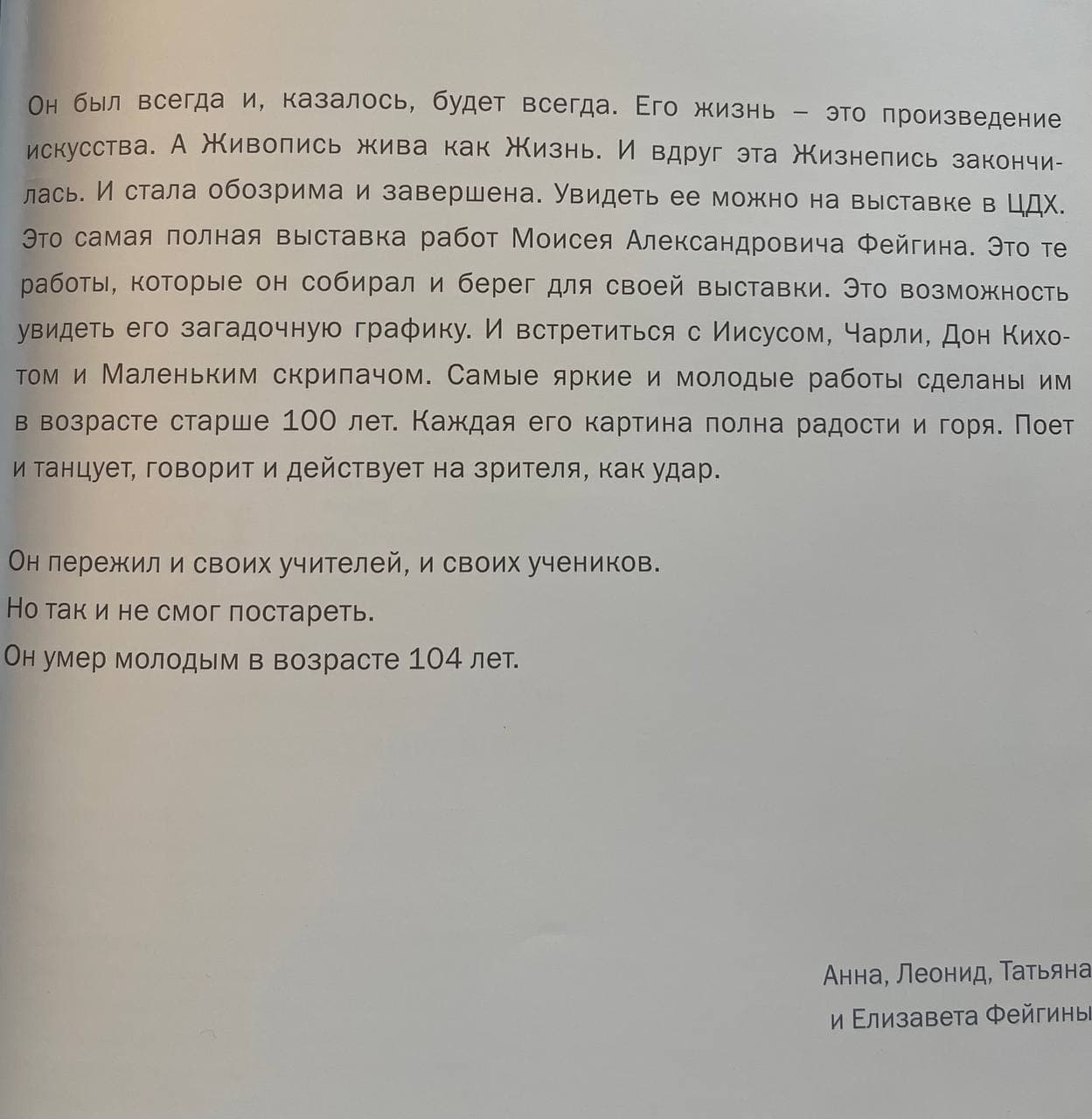

We should especially note that Feigin has no calm pictures. An internal pulsation and general tension are always felt in them. Moreover, the free movement of lines and colors is increasing from year to year. Not only at the age of seventy, but also at the age of ninety and, which is quite difficult to imagine, at the age of one hundred, he constantly expanded and asserted his plastic freedom. Looking, for example, at such canvases as "Figure Skating" 2005, "Composition in White" 2005, "Crucifixion" 2007 and some other works of 2007 that do not have a title. You understand that the soul of the master did not weaken after the partial loss of sight, the named works are comparable to his best works of the last three or even four decades. Suffice it to recall at least such paintings as "Happy Grandfather" in 1969, or one of the best canvases of 1993 "Round Dance in the Night". Regardless of the number of purely abstract works, it can be argued that real nature, starting from about the end of the 1960s, left Feigin's works, giving way to images of his fantasy that emerged from the world of literature, music, theater, and cinema.

The artist organically lasted and continued his series in the most natural way. Depicting Don Quixote with his faithful squire, Charlie Chaplin, the plots of The Return, dating back to Rembrandt's The Prodigal Son, endless clowns, jesters, harlequins, musicians ... It would seem that we are faced with a familiar world of eternal images that were painted by dozens of masters from Daumier to Picasso , from the artists of the World of Art to Tyshler and Fonvizin.

Nevertheless, Feigin cannot be confused with anyone. He has his own plastic tension, his colors, his own unique mixture of lasting drama and joy, his own love of life that draws into his cycle. Once upon a time in the column "profession" members of creative unions wrote - "free artist". Moses Feigin did not need to document this definition. He really was absolutely free and could repeat the proud words of Osip Mandelstam: "We will go through life, but we will not glorify either theft, or the day's work, or the lie".

Feigin's first paintings aroused great interest among the audience, who appreciated their powerful energy, contrast, and heightened emotions of the palette. In the thirties, the "formalists" were persecuted but Moses Feigin remained true to himself and worked in secret. For thirty years, only the closest people remained his only spectators. The artist's underground existence continued until the Brezhnev's thaw of the 1960s, when the maestro's works were gradually exposed to the public. Moses Feigin absorbed many styles and trends in his work - fauvism, cubism, post-impressionism, expressionism, realism.

(Based on materials from L. Feigin's website)