Bernardetta Palumbo, art critic, 2011

Russia’s historical path has often been characterized by exuberance, and by its uninterrupted quest for an identity of significance. The controversial events of the 20th century have compelled contemporary Russian generations to reconcile the events of this period, and to understand their value as a part of Russia’s collective memory. It is in this context that the work of artist Moses Feigin has been rediscovered within the past decade, and has taken its rightful place in the process of art history.

Feigin’s work has been celebrated posthumously with exhibitions in two of Russia’s most important museums—The State Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin Museum both in Moscow. Such recognition of the artist would not have been possible without collectors who prophetically recognized Feigin’s artwork for its importance within Russian art.

Collecting art requires passion and knowledge, but instinct is perhaps paramount to any collector’s success. Ms. Luba Matusovsky was guided by this instinct when she began collecting Feigin’s work. She was introduced to him through artist Irina Vilkovir. A brief meeting in the artist’s studio was the beginning of what developed into a warm and enduring friendship between artist and collector. Matusovsky remembers Feigin as a humble artist who led an extremely modest life. His broad knowledge was the reflection of an untiring curiosity. As a result, the artist’s work exhibits a rare variety of styles and techniques.

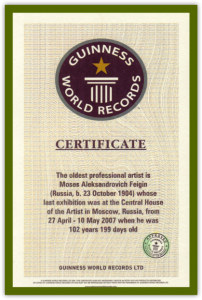

Some attribute the breadth of his art to his remarkable life span of 104 years! The Guiness Book of World Record recorded Feigin’s extraordinary age in 2008.

Unfortunately, the artist’s years did not add proportionally to what art historians know of him today.Not much was written about him, and almost everything known comes from first-hand accounts of those who knew the man. In spite of limited information, that which is known distinguishes him greatly.

Born in 1904 in Warsaw, Poland of a Jewish family, Feigin was the last member of the avant garde group “Jack of Diamonds” and a student of the Vkhutemas. After the political atmosphere drastically changed, he later became a respected member of the Union of Artists of USSR and adopted the style of the Stalinist years. Feigin was acquainted with Lentulov, Konchalovsky and Mashkov, and studied under Osmerkin and Popova. Through the work of one man, viewers have the opportunity to see a full century of Soviet/Russian art progress before their eyes.

If Feigin’s life was characterized by an assimilation of several biographical lines, similarly his artistic voice appears as an uninterrupted dialog with numerous important emerging artistic ideologies.Those familiar with 20th century art will not fail to recognize in his paintings rich references to the most important movements that included the works of Picasso, Matisse and Kandinsky. This amalgamation did not spare any style, and gives us an understanding of how Feigin responded to artistic thought quite different from his own.

Feigin’s reaction to Kandinsky is of little surprise when we consider that the latter was overshadowed in Russia by the attacks of the younger generation of Constructivists led by Alexander Rodchenko, an artist who in some ways represents the opposite of Kandinsky. The art of Rodchenko, who also taught at Vkhutemas, was focused on a constant quest for simplification. With this goal, the artist produced a few famous works such as “Rulers and Compass,” “Black on Black” and three 1925 monochromatic canvases defined by the critic Tarabukin as “the death of painting.” All these works are characterized by a severity of shapes and a minimalistic approach to color. The dramatic blackness of Feigin’s painting seems to embody a symbolic marriage between these two traditions. Ultimately, the struggle between the elements in the painting embraces Feigin’s ideal vision of the essence of art.

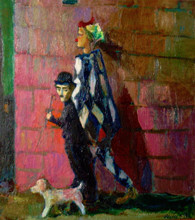

If a work like “Silence” is strongly interconnected with abstract experimentation, Feigin had no difficulty incorporating figurative tradition as well. The paintings produced in the 1980’s, many of which are included in Matusovsky’s collection, show an impressive amount of clowns and harlequins and refer to a precise tradition. The fascination with clowns and more generally with the circus was common between the artists in the 19th and 20th centuries. The figure of the clown belongs to the tradition of artists’ representations of themselves. Rodchenko’s fascination with the circus had its roots in the artist’s childhood, and remained a consistent subject throughout his whole career even when the artist’s primary focus was on photography. Beloved by the symbolists, the harlequins from the Commedia dell’Arte are a favorite topos of a writer like Alexander Blok and an artist like Konstantin Somov. In the West, the most famous instance of this tradition in the 20th century is Picasso’s so called “Italian period.”

(This period in Picasso’s art found its) beginning in 1917, when Picasso was working with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes on the gigantic stage curtain for Satie’s Parade. The curtains depict the classic Harlequin (the netherworld rogue) and Pierrot (the mute poet) seated backstage among other circus figures, watching an angelic equestrian reaching heavenward, guided by a monkey.[3]

According to Jean Clair, the harlequins and the clown-like figures provided Picasso with a functional metaphor to comment on the condition of his contemporaries.

The two works “Trio” by Feigin, produced in 1987 and 1988, are not only linked to this tradition but also seem to be in a direct dialogue with each other. When artist returns twice to the same topic it is often a sign of urgency to communicate something essential to his philosophy. Feigin’s harlequins share the enigmatic expression of Picasso’s creations.

Their profiles exhibit a severe, somewhat empty emotion. o this consolidated tradition, Feigin attaches a very personal note—the icon of mute cinema, Charlie Chaplin. According to the expert of Russian cinema Juri Civ’jan, there is no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown in Russia until 1922. Nonetheless, Chaplin became a very close figure to the Russian avant garde as attested by a beautiful series of sketches by the artist Varvara Stepanova. Among the others, Chaplin was particularly dear to the Russian Futurists, whose strong interest in cinema is well documented. Concerned with the topic of the machines and articulated movements, the Futurists recognized in him one of their paladins.

Once again, Feigin’s own vision seems to combine different traditions in a creative process that may recall the struggle of natural elements. The two paintings devoted to Chaplin from the Matusovsky collection clearly embody this struggle, as they focus on a series of strong contrasts. The noble, skinny, tall figure of the Picasso-like harlequin is countered by the short member of the working class—Chaplin.

The bright and warm colors of the harlequin’s outfit highlight the poverty of the little tramp. Interestingly, the semantic perspective almost makes Chaplin look like a child holding his father’s hand, maybe as a sign of the intention of drawing a direct link between the two traditions, or a symbolic passing from Commedia dell’Arte to mute cinema. While the representation of the two artists is detailed and accurate, the background is usually humble and does not present any ornament. The city is reduced to no more than a silhouette on a dark background or to a generic wall. The dog included lacks any specific features. The three figures of the title share a condition of profound isolation: They are outsiders. Traditionally, the “foreground entertainer is the original foreigner. He comes from outside, foris, and he lives out of the community.” (Clair, 30). As pointed out by Nadezhda Musyankova, Chaplin’s sad look is directed straight at the viewer, creating the impression that he, the artist, the outsider, shares this sense of lack of purpose with everyone. Ultimately, what can look like a comment on the artists’ condition can be extended to the human condition. The philosophical deepness of this message echoes several other artistic voices of the 20th century. From Beckett’s characters waiting for someone who never arrives to Chekhov’s decadent aristocracy stuck in a situation that never seems to change, culminating in the shameful final feeling of the protagonist of Kafka’s “The Trial.”

With its never ending exploration, Feigin’s art seems to place itself within the core of 20th century art. Instead of the result being paramount, this tradition places greater importance on the quest itself. In this pattern of different styles, Feigin’s own artistic identity emerges as an interrupted process of learning. His is an art that continuously nurtures itself with art. As Feigin once said, “The worse the life conditions, the better artists create. And vice-versa. Art rises from struggle”.

[1] http://www.gif.ru/persona/fejgin-time/

[2] Chipp, Herschel. Theories of Modern Art. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1968, pp. 155, 158

[3] Clair, Jean. The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist As Clown. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, p. 13.